Reproduction / Rosana Paulino / Backstage, 1997. Image transferred onto fabric, frame and sewing thread. 30 cm diameter

By Jész Ipólito and Thânisia Cruz

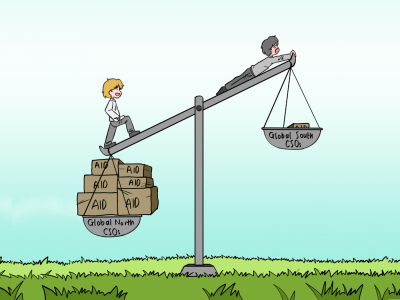

Philanthropy is presented as a strategy that turns the idea of donations into a notion of social investment capable of driving transformative actions for communities and groups in vulnerable situations. Despite its recent contributions to democracy, philanthropy is permeated with colonial aspects in terms of the distribution of resources around the world, which poses challenges to the beneficiaries. This is what we understand from the article “Is the Decolonization of Philanthropy Moving Forward?”, written by Allyne Andrade e Silva and Graciela Hopstein, for Comuá Network.

Within this context, the experiences of black clubs, associations, brotherhoods and personalities appear to cause surprise when confronted with the world of philanthropy.

In 2019, Tyrone McKinley Freeman wrote about “Black Donations over the Years”, where he recounted countless cases of black individuals who have donated to abolitionist, educational and social justice causes in the United States since the 19th century. This model of giving generated and distributed within black communities continues to exist. However, it now seems to take place on a much larger scale. So, what was once done, but not named, and sometimes done in secret to ensure the safety of black people, has become Black Philanthropy Month, celebrated in the United States in August.

One of the sources on the subject shows that Black Philanthropy Month was created in 2001 by Dr. Jackie Bouvier Copeland, founder of The Women Invested to Save Earth Fund (WISE), which is currently the incubator of the black philanthropy program. Over the years, fourteen campaigns have been executed on this theme, the first of which, in 2006, “Black Women Donate: Moving towards a Global Movement”, was deeply emblematic for these reflections raised by the Comuá Network in September 2023.

In the Month of Philanthropy that Transforms, the Comuá Network has embraced countless debate initiatives, webinars, research launches, face-to-face and online activities throughout the month. It was within this context that the online event led by black women on the field of philanthropy in Brazil took place, and it is these inputs that will be presented in this two-article sequence.

Black philanthropy in Brazil

If we are interested in analyzing intra-community donations in Brazil from the perspective of the associative actions of the black population, we can also look at the arrangements made by writers, greengrocers and religious groups who paid for the freedom and education of their peers. However, when it is referred to as black philanthropy, it happens differently and involves more recent aspects of action.

In terms of inequality and racial conflicts, Brazil and the United States share common experiences, and that is how black philanthropy reached Brazil with greater affluence after the global repercussions of the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd in 2020, as a result of the rapprochement of organizations from both countries that collaborated with actions to build racial equity.

In Brazil, aspects of this black philanthropy took a different turn. If, from the political angles of freeing black people and establishing a social movement, black communities need to develop as self-sustainable, in raising and distributing their donations, within the context of promoting black philanthropy, the Brazilian black population does not have sufficient assets to see to and ensure the turnover of the funds as in the past.

This is not to infer that black philanthropy is comfortable in the United States, as 12.5% of the country’s population is black and there are only six black billionaires (Forbes, 2020), who are also cited as philanthropists on different occasions. This means that, even if there are community actions or people with incomes that make millionaire donations possible, the effort to achieve equity through social investments can be deemed negligible.

So, what we know as “Black Philanthropy Month” in Brazil is likely the repercussion of the work of a few black female managers working in social investment funds, pointing the way to resources. In other words, the financial contributions intended for black philanthropy reach black organizations in a limited way and are not managed entirely by black people at the source, thereby causing civil society organizations to remain in a fragile state, especially collectives and organizations in the north and northeast regions.

At the moment, in Brazil, this precariousness in driving development democratically and looking to those who know how the resources should be used, adds to other political demands of our time, such as the concept of autonomy that is not achieved with colonial resourcing dynamics, as Allyne Andrade pointed out in her text.

In addition, the report titled ‘Where is the Money for black feminist movements?’ by the Black Feminist Fund, presents crucial data for an in-depth analysis of the situation of black women’s organizations and groups on a global scale. Only a tiny fraction, ranging from 0.1% to 0.35%, of the donations made by foundations around the world go to black women, girls and transgender people. This shows an alarming disparity in the funding of initiatives led by black women. In regard to annual budgets, it is worth noting that more than 60% of black feminist organizations operate with annual budgets under 50,000 dollars, highlighting the scarcity of essential resources to carry out their crucial mission. 81% of these black organizations do not have enough resources to achieve their goals.

The co-founder of the Black Feminist Fund, Hakima Abbas, invites us to think collectively about the global scenario of philanthropy for black women, mentioning feelings that are unique to black feminist groups: pain, frustration, exhaustion and perpetual resistance. The report affords an opportunity to reflect and act towards the practice of anti-racism by developing a culture of giving and philanthropy emerging from the people who know what needs to be done. In this sense, black philanthropy in Brazil faces challenges within a global context of inequality and lack of funding for initiatives led by black women.

Black women’s organizations dialoguing about black philanthropy in Brazil

Faced with the differences in doing philanthropy that keep us black, the aim is to listen to what the reality of black women shows us. We are looking for a way of doing philanthropy where we can go beyond where we are, using resources that are more effective and a form of governance that allows us to be who we are, without having to adapt our content to fit into a philanthropy that moves away from us. In this context, the experiences shared by Valdecir Nascimento, Halda Regina, Durica Almeida, Maria Malcher and Terlúcia Silva during the online meeting “Narratives of black women on the field of philanthropy in Brazil” on September 25 of this year revisited crucial issues concerning black philanthropy in Brazil.

Difficulties to raise funds, dependence on national calls for proposals, the importance of flexible resources and valuing black culture are themes that permeate the discussion on how to direct philanthropic efforts more effectively. In addition, the emphasis on political training, black women’s activism and passing the baton to youth shows the need for inclusive, progressive approaches in philanthropy aimed at black organizations in the north and northeast regions of Brazil. In the next article, we will explore the specific reality of philanthropy for these organizations, highlighting the peculiarities of the regions and the strategies to overcome the challenges they face.

NOTE: This article is part of the results of the research project “Narratives of Black Women on the field of Philanthropy in Brazil: perspectives for the future from the North and Northeast”, by scholarship holder Jész Ipólito, under the Comuá Network’s Saberes Program.

AUTHORS:

Jész Ipólito is a Saberes Program scholar, black feminist activist and communicator & Thânisia Cruz is president of the NGO #ElasNoPoder and coordinator of the Katendê Project.

Translated by Dayse Boechat